It is probably not a good sign when a funeral service is more encouraging than a political debate between the only two plausible candidates for the next four-year term of the presidency of the United States, but such was my experience toward the end of last week. The debate came first, but I shall deal with it only briefly, as, Number One (as one of the debaters said repeatedly) it has already been the subject of a vast amount of commentary from professionals at all levels of the commentariat, and Number Two, it was such an actual disaster for President Biden and the Democratic Party and so unspinnable that it would be shameful even for a party hack to try. Mr. Trump lied incessantly during the debate, but he did so with a comparative coherence, and he even had several sentences in which could be detected a complete thought laid out in proper form with a subject and predicate in the right order. As I write this the Democratic panic of the first post-traumatic period has perhaps somewhat abated. I now doubt that Biden will voluntarily withdraw or be forced out of the contest, as seemed at least possible in the frenzy of Friday morning.

Elective politics is always a choice among imperfect alternatives. It often enough demands invocation of the adjective “realistic” and the phrase “the lesser evil.” But how can a dynamic nation of three hundred and fifty million be presented with the choice that now presents itself? I have several lovely grandchildren. Am I supposed to claim that I am untroubled by the reality that Joe Biden, for all his undoubted good intentions and bumbling avuncularity, should be the guardian of the atomic codes? That Trump lies habitually does not exonerate the pious fraud of prominent Democrats who have for so long assured us that, behind the scenes, Biden is a sort of combination of Metternich and John Chrysostom.

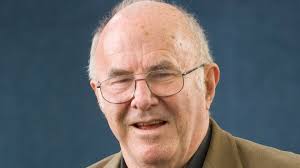

So much for Thursday night. I now turn to the paradoxically happier subject of the memorial service. A few years ago a dynamic and charismatic Englishman, Will(iam) Noel, took up a leadership position in our University library system. He was a Cambridge-trained historian, a medievalist, and a cutting-edge innovator in library science. He had spent some years at the Walters Gallery in Baltimore before moving to the University of Pennsylvania libraries. The Penn library—including its rare book and manuscripts division—was superb in my own fields of special study even before the founding of the Schoenberg Institute for Manuscript Studies about fifteen years ago. At the center of this enterprise was the huge gift of medieval and Renaissance manuscripts—valued at the time at about twenty millions, though in fact priceless--made by Mr. Lawrence Schoenberg. Will Noel was the director of this enterprise, and how Princeton lured him away from it I cannot know and would never be allowed to say even if I could. I was already well retired by the time he got here. I was alerted to his moving to Princeton by close friends who had known him in Baltimore. As a long-time booster of Princeton’s Firestone Library, and as an active member of the Friends of the Princeton University Library I came to know him only slightly, but well enough to be mightily impressed.

Two or three months ago Will Noel was in Edinburgh with some professional colleagues on some library-related business. As he was walking on a sidewalk, an out-of-control vehicle flew off the roadway onto the pedestrian sidewalk and struck him. Of the group with whom he was walking he alone was seriously injured, but very seriously indeed. He survived for a while hospitalized in a coma, but not for long. He died on April 29th. The accident was of the malign, senseless, and indeed incomprehensible sort that challenges my increasingly desperate attempts to continue to believe in Providential Order. It snuffed out the life of a brilliant and innovative scholar at the height of his powers. But before that, the scholar was a husband, a father, a brother, a friend to many, a colleague to many.

This breadth of the loss was not the primary focus of the beautiful memorial service that took place last Friday, however. The tragic sense was not suppressed but overwhelmed in the best sequence of brief but powerful personal reminiscences I have ever heard at such an event. I was able to attend with my Baltimore friends, one of whom, Charles Duff, was among the eloquent speakers. The Princeton University Chapel is a mini-Amiens Cathedral and one of Ralph Adam Cram’s greatest masterpieces. I don’t know the precise seating capacity of the building, but it must approach 2,000. It was probably three quarters full. As you grow older, you find yourself attending more and more obsequies. And If you write a regular blog, you find yourself writing more and more obituaries. In recent years I have had to memorialize four of my own dearest friends: Michael Curschmann, Robert Hollander, Joseph Trahern, and most recently Andrew Seth. Will Noel was not a close friend, rather a much-admired acquaintance and professional colleague, but his comparative youth and unfulfilled projects add a particular sorrow to the brutal caprice of his death.

Anyone inclined to think that library science or codicology (the study of codices, or manuscripts) are dull, arcane, or dry-as dust pastimes would, I believe, soon be disabused of such notions if they could meet a fine teacher who was also a fine codicologist. You can put my premise to the test with little expenditure of time--though with a substantial risk of intellectual excitement--by viewing a Ted Talk Will Noel gave more than a decade ago, about the Archimedes palimpsest then on display at the Walters Art Gallery. * Archimedes, perhaps the most famous ancient scientist known to us by name and a body of written work, flourished in the third century of the pre-Christian era. In the earliest periods of book making, the materials needed for their manufacture were costly and sometimes difficult of access. Under these circumstances obsolete books with vellum (animal skin) pages were often scraped down and reused, usually leaving a faint, sometimes shadow-like impression of the original writing. Such a book is called a palimpsest from a Greek term meaning “rubbed smooth again.” The Archimedes palimpsest is part of a hand-made thirteenth-century prayer book. Scrupulous, patient scholars have deployed their skill, erudition, and some cutting-edge scientific instruments to decipher the erased text lurking within its recycled pages. Lo and behold, they found passages of previously unknown works of the celebrated philosopher. Forget the baloney in the Da Vinci Code. This is the real thing—original writings of the most famous ancient Greco-Roman scientist known to us. His most celebrated saying, or at least his most popular one, concerns the Law of Levers: Give me a lever long enough and a fulcrum on which to place it, and I shall move the world. It is by no means grandiose to suggest that something spiritually analogous can be said of those scholars like the late and very much-lamented Will Noel.

Thursday night was sad, somber, and depressing. Friday morning was by contrast inspirational and encouraging. There are few enough institutions in our society that seem to me both essential and unequivocally good. Some of those dealing earnestly with cultural preservation and education are among the best. The outpouring of love, appreciation, and admiration evident in that memorial service were first of all emblems of the esteem in which a particular man was held by so many. But in a larger social sense they were likewise gestures of support for what is the larger cultural mission to which thousands of scholars and teachers are eager to devote the work of a lifetime, and indeed to the enterprises of the spirit and the intellect generally. So the end of the week turned out to be for me a kind of temporal palimpsest on which distress had been overwritten in uplift and hope.

*https://www.ted.com/talks/william_noel_revealing_the_lost_codex_of_archimedes?language=en&subtitle=en&trigger=15s