The constraints of the pandemic have proved trying for us as for everyone else, especially as they have coincided with those of aging. The cloud’s silver lining has been an enforced leisure. Though I have not exploited it as I undoubtedly should have, indeed though I have sometimes found it rather trying, it has allowed me the time and the impetus to think a little more deeply about certain questions that have long interested me. Against the backdrop of really terrible world and national problems, I have had the luxury to read and think about art, literature and music with licensed self-indulgence. Mark Twain famously said that “A classic is something that everybody wants to have read and nobody wants to read”. Quite a crack, and too close to true. I now realize that as a young man I invested much time in reading classics of this sort, books that I didn’t quite “get” but I knew on the excellent authority of somebody else were very good for me. One of these was Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Marble Faun. I didn’t get it at all, but about thirty years later something of Hawthorne’s plan may have dawned on me when I started reading Henry James seriously and began to understand the degree to which so many nineteenth-century American intellectuals were ambivalently fascinated by Old Europe, and especially by its opulent artistic heritage. One never stops learning, thank God, and I may have progressed a little further in understanding this matter on Friday last.

The pandemic has surely been particularly severe for elderly people who have been isolated or solitary. We have been blessed to enjoy the constant, cheering support of our children and grandchildren and, at the local level, numerous good neighbors and friends. One of these, who is both a former student and a former colleague, has done us innumerable kindnesses. It was he who on Friday drove us door-to-door to Philadelphia to visit the art collection of the Barnes Foundation. This was our first visit , but I certainly hope not our last.

Albert C. Barnes (1872-1951) was a Philadelphia physician who accumulated considerable wealth by developing an eye medicament called Argyrol. As sources of nineteenth-century baronial fortunes go, Argyrol had a good deal more social beneficence than most. Barnes had developed a serious interest in art, especially what was “modern painting” around the year 1900. While not exactly a conventional philosophical deep thinker, he had definite ideas about aesthetics and the educational role that art could play in public life. He had a pioneering sense of the potential role of elite art in a democratic society. It was with a large if at first unformed sense of social mission that he set out energetically and purposefully to construct a great collection of paintings. In retrospect his success seems nearly incredible. He was the right man in the right place at the right time. Barnes was a high school chum and artistic soulmate of William Glackens, a prominent leader of the “Ashcan School” of painters, and a man with a faultless eye. As Glackens was setting off for a trip to Paris in 1912 Barnes slipped him a line of credit in the amount of $20,000 with a commission to buy up some post-impressionists of the sort both men admired. It was not the most famous transatlantic voyage of that year, as it evaded icebergs, but it was of signal importance in the history of American art collections. At the time Barnes was particularly interested in Renoir. Glackens was able to negotiate essentially wholesale prices and scored thirty-some now priceless works by Renoir, Cezanne, Van Gogh, Picasso, and others. Twenty grand was a lot of money in 1912, but still…Such was the nucleus of one of the greatest private art collections ever constructed in America—or anywhere else, for that matter.

Barnes’s private residence was in Merion, a ritzy Main Line suburb west of Philadelphia, and it was there that the treasures were housed. Once started in his self-conscious role as collector, it was full steam ahead, and he never again bought a painting he had not himself first examined. He read voraciously among the leading art authorities of his day, and he cultivated personal friendships among artists and intellectuals, particularly the educational guru John Dewey, a fellow patrician democrat in the Emersonian tradition. By the 1920s, his collection burgeoning, he built a separate gallery in Merion to house it and established a foundation to preserve and shepherd it.

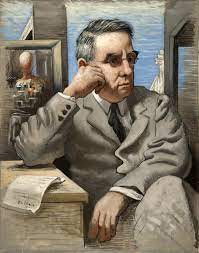

Giorgio di Chirico: Albert C. Barnes

There is much more to be said about Barnes the man, but I need to say at least a few words about the paintings. He had very definite ideas about how they should be displayed. When in an act of the highest philanthropy—a word meaning the love of mankind—he gave them over for public access, he did so in a narrowly framed will that required them forever to be displayed in the Merion gallery and in the exact spatial configurations in which he had left them at his death in 1951. Residential Merion, PA, was never a great site for a public museum intended to attract crowds. It became ever less so in the next five decades. A half century after his death the Foundation eventually gained legal authority to build a new and magnificent gallery, itself a work of art, on Philadelphia’s “Museum Row,” and to remove the paintings to it. But his personal (eccentric?) concept of presentation continues to be honored. That is, the paintings are displayed in the clusters or groupings (he called them ensembles) exactly as they were in Merion.

ensemble presentation

Barnes thought painting should be appreciated with as little intermediation as possible, with a minimum of textual explication. (This was also the theory of the “New Critics” behind the teaching of poetry in my undergraduate years in the 1950s). Most of the paintings merely have small brass plaques with the artist’s surname. As for their organization on the walls, arrangement is not by artist, period, or genre. The controlling principles seem to be harmony of size and placement. The collector’s principal interests naturally took him to what was for him recent or contemporary, so there is a lot of the late French nineteenth century. But along the way he picked up classical artefacts, African art, and numerous old masters. So you will find an El Greco flanked by a French post-impressionist and a panel separated from a medieval altar, if the sizes seemed right. He also loved Pennsylvania Dutch “primitive” cabinets and dowry chests, one of which is centrally placed in most rooms, and little bits and pieces of old forged iron. And through it all runs the bright red thread of thought touched upon in my initial paragraph: questions of the universality of art, the nationality of its expression, the possibilities of its democratic appreciation and influence. Maybe that’s what The Marble Faun is about, though I somehow doubt it.

Around the periphery of this fabulous modern collection are some almost accidental delights for a medievalist. One that surprised and captivated me is a small panel (“Westphalian, About 1400” says the little brass marker) of Dives and Lazarus, otherwise known as the Rich Man and the Pauper (Luke 16: 19-31). My Franciscan preachers loved this text’s apparent support for their doctrine of evangelical poverty. The chief indication of the wealth of Dives seems to be his very classy hat. But the context in which I came upon this surprising piece complicates the usual interpretation of the parable. Barnes was a rich man whose private wealth is now the public good of thousands.