One more word about teaching what the world ought to be: Philosophy always arrives too late to do any such teaching. As the thought of the world, philosophy appears only in the period after actuality has been achieved and has completed its formative process. The lesson of the concept, which necessarily is also taught by history, is that only in the ripeness of actuality does the ideal appear over against the real, and that only then does this ideal comprehend this same real world in its substance and build it up for itself into the configuration of an intellectual realm. When philosophy paints its gray in gray, then a configuration of life has grown old, and cannot be rejuvenated by this gray in gray, but only understood; the Owl of Minerva takes flight only as the dusk begins to fall. [Die Eule der Minerva beginnt erst mit der einbrechenden Dämmerung ihren Flug.]

G.W.F. Hegel, Preface to the Philosophie des Rechts

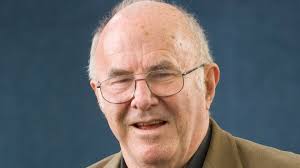

In the course of this essay I shall attempt to comment on the meaning in this famous passage, at least to the uncertain extent that I understand it myself. I hope that its main point—a personal application of a frequently quoted epigram made by a philosopher of history--will be reasonably clear. The subject might be defined as the sadness of the search for wisdom. But it requires the somewhat breathless introduction of three important thinkers. They are (in an order both chronological and alphabetical) Augustine of Hippo, Georg Wilhelm Hegel, and Clive James. The three men were very different one from another; yet they shared the crucial commonality of intellectual brilliance deployed upon challenging and consequential subject matter, and extraordinary powers of verbal expression in deploying their ideas. Augustine (354-430) was a North African Roman who became the most influential theologian in Western Catholicism. Hegel (1770-1831) was a German philosopher of huge intellectual ambition and influence; and Clive James (1939-2019) was an Australian born journalist and cultural critic who spent most of his life in the intellectual and professional milieux of London.

Hegel and Clive James are linked for me because of James’s brief but brilliant biography and assessment of him in one of his wonderful essays in Cultural Amnesia.* If you don’t know this book, I strongly recommend it to any reader with an interest in our cultural history and an appreciation of fine English prose. It is a collection of a hundred or so brief biographical essays. Speaking of the famous remark about the Owl of Minerva, James says: “Hegel’s prose could be very beautiful like this.” Yes, but he immediately adds: “After his death his prose became famous for being unyieldingly opaque, and indeed much of his later prose was.” I am no expert on Hegel and have found trying to understand him too hard a slog to claim confident success. Clive James’s six-page essay devoted to him in Cultural Amnesia is one of the clearest, most succinct treatments of a truly towering philosopher I could imagine.

A second famous passage comes from Augustine’s autobiography, the Confessions, and provides a kind of parallel. It is an address directly from the author to God: “Late [or, probably better, too late] have I loved thee, O Beauty so ancient and so modern”. (Sero te amavi pulchritudo tam antiqua et tam nova.) Hegel and Augustine share the idea of “too lateness,” but in rather different senses. Augustine berates himself for time wasted in futile or errant philosophical searches. Hegel seems to be announcing a morose law of intellectual history.

It will probably be apparent why the themes raised here might impose themselves upon the reflections of a scholar in his old age. I have devoted a great deal of my life to studying and writing about “many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore.” I am not sure that the owl has ever appeared in my barn loft, but the raven is sure to before very long. It’s only a question of time.

In the ancient moral vocabulary, writers make a distinction between two Latin words, scientia and sapientia. The former, scientia, is usually translated as “knowledge”, sapientia as “wisdom.” The two obviously related concepts are not identical. Wisdom is the moral fruit of the proper use of knowledge. We all, or at least most of us, believe in some form of this idea. Another famous formulation we owe to Pascal in the seventeenth century: “The heart has its reason which reason knows nothing of…We know the truth not only by reason, but by the heart.”

It is at least a curiosity that the symbolic association of the owl (bubo) with wisdom has continued in popular iconography until our own day. Minerva is the goddess of wisdom. Her Greek equivalent is Athena. Her avian emblem, the owl, which once brought the dignity to Athenian coinage that the eagle now sheds upon the American, has largely been co-opted by Walt Disney and seems to represent a kind of endearing avuncular amiability. There’s nothing wrong with that, but Athena’s bird was more venerable, solemn, indeed magisterial. Wisdom--a thing different from intelligence or even intellectual brilliance, and certainly different from amassing a boxcar load of quaint and curious facts—seems to be a reward for an attitude rather than the achievable goal of a program of long and scrupulous search.

It is only natural that a scholar, given the opportunity to look back in review, might want to reflect on the distinction between knowledge and wisdom. Learning offers its great contributions to one’s life, but it is not a substitute for living. The great French historian Jules Michelet—and I do mean great—is reported to have made the following sad remark late in his life: “I have passed along the side of things, for I mistook history for life.” Among the four or five most fecund legends in our literary culture is that of Dr. Faustus, usually called the “Faust Legend”. Remotely based in the memory of an actual Renaissance savant, it records the fictional history of a scholar of great learning who makes a pact with the Devil. In exchange for a period in which he will enjoy great wealth, prestige, and sexual pleasure, the scholar will give up his immortal soul. Selling one’s soul has become proverbial. The legend appears in practically all forms of early popular literature—folklore, ballads, broadsheets. In English literature it is enshrined in Christopher Marlowe’s powerful drama; but its most famous appearance in the literature of “high culture” is in Goethe’s lengthy poetic drama, Faust, which appeared in two parts in the early nineteenth century. This work is often regarded as the greatest achievement in German, and indeed one of the greatest in world literature. In Goethe’s treatment of the Faust legend, the appetite for universal erudition is paralleled by gross carnal cupidity and criminal indulgence.

Everyone must have some definite concept of the “mad

scientist,” a man whose scientific investigations have driven him to the brink,

and sometimes over the brink, of lunacy.

Who is likely ever to forget Dr. Strangelove as presented by Stanley

Kubrick and Peter Sellers? But there are

mad humanists galore as well. I speak as one who spent half a century teaching in

liberal arts departments of a major institution, and as I scan our contemporary

cultural landscape, I find some of our madder humanists only slightly less

alarming than Dr. Strangelove, our updated Dr. Frankenstein. It is the link between erudition and madness

that makes what I shall call the “real world” so chary of it. The “Acts of the Apostles” (cap. 26) gives an

account of Paul’s verbal self-defense before Festus, the Procurator of

Judaea. “And as he thus spake for

himself, Festus said with a loud voice, ‘Paul, thou art beside thyself; much

learning doth make thee mad’.” Has the scientific quest that led to a hydrogen

bomb or the technological deployment that led to the overheating of the earth’s

entire atmosphere exceeded the bounds of moral capacity? And the questions that seem so tremendous on

the cosmic scale do have their echoes in the twilight lives of aging scholars. The

concerns that crowd the mind are hardly of a Faustian grandeur. They are small, personal, quaint, perhaps even

droll, but no less disquieting as we strain our failing ears listening in

doubtful hope for the sound of the whoosh of a huge owl’s flapping wings. Too late?

*Clive James, Cultural Amnesia: Necessary Memories from History and the Arts (W. W. Norton: New York and London, 2007), pp. 876.

A most engaging article, Professor Fleming. I, too, am aware of flapping wings and trying in various ways to be prepared. I am about two years your senior in age--and only in that category and have yet to achieve a healthy resolution.

ReplyDeleteOnly one thing: I'm surprised you didn't mention Peter Brown in connection with Augustine.

Best wishes, Gene McHam