My last essay had to do with attempts to coerce language to conform to social and political ideas of our fancy. This one begins with a meditation on language that has become so formulaic that we seldom think about it at all. In the household doldrums of Covid-world we have tried, probably unconsciously, to make something out of very little by anticipating the daily arrival of the mail. Since the invention of email real letters are virtually unheard of,* but if you are desperate, you may actually cast an eye over the abundant junk mail, and if really desperate you may even be likely to open it. For the past couple of years I have received, maybe once or twice a month, a letter from a land company offering to buy from me some acres I own in the Ozarks. I deduce there are land agents all over the country sifting through tax records in county court houses. But not a chance! My grandchildren will decide how this little bit of gorgeous wilderness will be shared with the world in its natural state and quite without the help of a “developer” whose return address is a post office box in Sparks, Nevada.

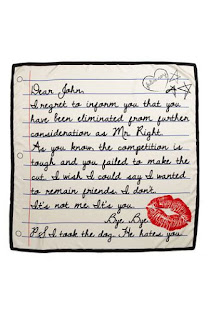

I opened a letter that began…Dear John…I felt annoyed and aggrieved, irrationally, and for more than one reason. The man signing the letter, Wilbur Somebody, didn’t know me from Aristotle, but presumes to address me by my first name in the hopes of bulldozing cedar trees and putting up a ticky-tacky split level. Furthermore, that name itself, John, is regularly used to denote such things as a prostitute’s client or a toilet. Furthermore yet, a “dear John” is a specialized form of an unwanted missive that revived unhappy adolescent memories. These associations are not Wilbur’s fault, exactly, but Wilbur was what I had at hand to be annoyed by. It was the word dear that I focused upon. Everybody who writes to anybody calls that person dear. But surely they don’t really mean it. They cannot possibly even think about it. Dear means esteemed, held in affection, beloved. As an epistolary salutation, dear is a meaningless convention. Yet I use it all the time and shall presumably continue to do so for the remainder of my days. Why? Will “Dear” just lie there in the linguistic pool, soggy and motionless forever?

Dear is another one of those good old Germanic words that were part of the vocabulary of early speakers of the English language. It was destined to be the homonym—homonyms being words with the same pronunciation but differing meanings—of the generic quarry of game-seeking hunters, the deer. I’ll come to that in a minute. The other, related meaning of dear had to do with commerce. Dear means costly, expensive. Though now rarely used in that sense in American English, it is still alive and well in many other places in the English-speaking world. Any port in a storm. That little chain of associations was useful as it transported my mind from Wilbur’s insolence and his road-graders to something more interesting, namely the commercial binary of dear (expensive) and cheap.

Now, this is really interesting. Upscale goods proved in time to be too good for a four-letter Anglo-Saxon adjective. They deserved something Latinish, something Frenchy. Expenditure invokes the heaviness of precious metal bearing down on a hanging (dependere) scale. The focus of the word was originally on the purchasing power of the buyer rather than on the quality of the goods. Expensive is, so to speak, an expensive word. Dear was a cheap one. But, we notice, there is no expensive word for cheap, just cheap cheap on its own. The root meaning of cheap was “market”. The social and economic importance of markets in earlier European societies could easily be supposed even without the abundant linguistic evidence of place names in many European languages. English Cheap Sides, East Cheaps, Chipping Nortons and a hundred other ch-p variants are scattered across the Ordinance Survey maps of Great Britain to this very day. Descendants of the Latin mercatus (market) became more common after the Norman Invasion, so that we still speak of “market towns” and find numerous place-names like Downham Market.

I don’t know whether free-market economists like Milton Friedman have sufficiently exploited the etymological encouragement for their theories possible to be found in historical dictionaries. But ceap, market, is a word consumers usually like. In French the Latin-based marché shows the same tendencies. The French version of “cheap” is à bon marché—at a good market price, I suppose. One of the classic large Parisian department stores was called Le Bon Marché. No American retailer of class would put “Cheap” in the name of a store today. But French bon marché has not yet been wholly degraded. It’s more like “great bargain.” But the distinction between “great bargain” and “cheap and nasty” is on a sliding scale. The mountains of synthetic junk that now clutter flea-markets and yard sales in my part of the world are evidence enough of that. It well may be that the excellent English adjective tawdry derives from the name of a Dollar Store medieval market called the Fair of St. Audrey (‘Taudrey”), Audrey being the popular name of a royal Anglo-Saxon saint, Etheldrida! Classy name, but crumby stuff.

So were I to respond to the unsolicited letter from my Nevada land speculator, the proper salutation should probably be…Cheap Wilbur…cheap in the American sense, of course.

The homophonic pairing of dear/deer, though irrelevant to most of what I have said so far, does illustrate another interesting linguistic phenomenon, the oscillation between generic and specific. The modern German adjective for what I shall call economic dear is teuer. The modern German word for “animal” is Tier. It is obvious that English deer came to refer to a specific group of large animals frequently hunted by our ancestors. In English, but not in German, the two words came to have the same pronunciation. Something rather similar manifests itself in what you eat after you have killed the deer, namely meat. But in early English meat was the generic word for all sorts of food. There are a few residual memories of this: sweetmeats, the meat of a walnut. But your average hairy-chested Old English huntsman was no Vegan. He wanted his meat to bleed. Your hairy-chested Anglo-Norman huntsman, on the other hand, was likely to be an aristocrat as interested in the chase as in the game—both words that suggest that the business had as much to do with sport as with alimentation. But he too ate what he killed—venison, from venatio (hunting.)

*No sooner had I written this than we got a real letter from our dear granddaughter Ruby at summer camp!

McDonalds came a cropper in East Asia trying to sell "Value Meals" -- burger/fries/soda for a better price than the three bought separately. There were two problems: (1) if there's no rice, it's not a meal, period. But (2) what does "value" mean? Well, something like ceap. But try as they would to translate, they couldn't get past calling their handsome repast the equivalent of "cheap snack", and that just had no viability in the marketplace.

ReplyDelete