I have never been good at dates, a liability manifested early in my meager social life as an adolescent and later in my repeated chronological confusions in mastering the canon of Chaucer’s poetry. With Medjools I have done somewhat better--but who wouldn’t? Yet from time to time a calendrical date does stick in my mind, and the sticky one at the moment is 1749.

I have several times written essays relating to the beautiful colonial farmstead that our elder son Richard and our daughter-in-law Katie Dixon have in Hunterdon County NJ near Frenchtown on the Delaware River. Well, very good friends of ours in Baltimore, Charlie and Lydia (Belknap) Duff, know about it too; and they just made Richard and Katie a lovely gift. Since the gift’s recipients were living in Spain at the time, it came to me as an intermediary. It is an elegant large-format scholarly monograph written by Lawrence Henry Gipson and published by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in 1939. Its title, and of course its subject, is Lewis Evans. I had never heard of Evans, but I knew a little about Gipson, enough to make me read the book myself. Lewis Evans was a pre-Revolutionary Welsh-American surveyor and geographer who in 1749 published in Philadelphia what I learn is a famous monument of early American engraved cartography—a map of the “middle colonies,” New York, New Jersey, eastern Pennsylvania and Delaware. More or less in the map’s center is the Hunterdon County forest at Kingwood, where Richard and Katie’s house would rise some thirty years later. While engaged in a library downsizing operation, our generous Baltimore friends thought of this Kingwood property. There are pioneers and pioneers. The cartographer Evans anticipated the Lewis and Clark expedition by half a century! I already knew something, a little, of L. H. Gipson, a famous American historian of the first half of the twentieth century. Admittedly I had never read a page of his fifteen-volume magnum opus about the British Empire before 1776. What I knew was that in 1964, when I was teaching in my first job at the University of Wisconsin, Gipson had been one of the small band of surviving members of the first American class of Rhodes Scholars (1903) to matriculate at Oxford. There had been a reunion of these legendary veterans that had been much bruited about in the Rhodes world, and I had followed it in the press.

Evans, though he left a spare biography, was well known among the fledgling scientists of pre-republican North America. The naturalist John Bartram, with whom he published A Journey from Pennsylvania to Onondaga in 1743 (printed by Benjamin Franklin) called him “a queer fellow”--perhaps a compliment roughly equivalent to “ingenious” among early boffins. His map is hardly beyond criticism. You certainly wouldn’t want to use it to try to drive to Allentown. But you can see from this lavish book how extraordinary it must have appeared to the frontiersmen of 1749.

I already knew when examining this book that one publication of 1749 must bring another to mind. For I am a true believer in the theory of the association of ideas often attributed to Locke, and perhaps for me most memorably preserved in our classical literature in the opening pages of Sterne’s Tristram Shandy. During the very coital act destined to bring Tristram into the world his mother’s mind is seized by a pressing question: did anybody wind the clock? For forty years I have been telling students that this is a marvelous comic exemplification of Locke’s associative theory, and urging them to watch out for stray thoughts wanting to intrude upon their private moments. That’s not exactly wrong, but just now, in nosing about a bit, I discovered that the more powerful expression of the associative theory was in David Hartley’s Observations on Man published (naturally) in 1749.

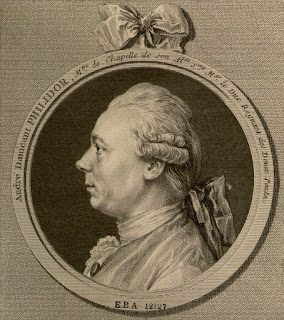

François-André Danican Philidor (1726-1795)

Hartley was new to me but my mind was already seized of another epoch-making publication of that year. I am a chess player, and my son Luke is a really good chess player. One of the great figures in the history of chess, whom I have studied intensively, is the French musician François-André Danican (1726-1795), best known as Philidor, the honorific name bestowed upon his numerous musical family forebears in an earlier generation. This Philidor was one of the tragic geniuses of the late Enlightenment. To be the premier opera writer of eighteenth-century France is not the same thing as being the premier opera writer of eighteenth-century Italy, but it’s not chopped liver either. And to be that and a chess genius and the author at age twenty-three of the revolutionary Analyze des Echecs—probably best translated simply as Chess Theory—is really something. I am not a rare book collector, but I do own a copy of the first edition, published in 1749 in French but in London, under the patronage of the Duke of Cumberland, third son of George II, alias the Butcher of Cullodon. That is one of few bibliographical distinctions my private library could share with those of Rousseau, Diderot, the Baron d’Holbach, Ben Franklin, and Thomas Jefferson, among dozens of the chess fanatics of the late Enlightenment. Philidor’s revolutionary approach to the game was summarized in his epigrammatic doctrine: the pawn is the soul of chess. I am convinced that the book was literally revolutionary and an influence on the famous pamphlet published forty years later, a few months before the storming of the Bastille in 1789, by the Abbé Sieyès: What Is the Third Estate? The third estate was of course the vast majority of ordinary Frenchmen who were not nobles or clergy. Sieyès didn’t say it was the soul of the state, but he came close. Yet Philidor, insufficiently woke for the likes of Robespierre and the Committee on Public Safety, died a banished man in London with a price on his head in his native land.

Sitting here at the distance of the new year of 2022, that’s a fair amount of excitement for the year 1749; but you could doubtless find commodious, interesting, or provocative synchronic connections for practically any date of your choice. There are of course printed annals, and now Wikipedia pages—organized precisely by year and indeed by month--designed to help you do just that. I must say, I cannot recommend Wikipedia for this, however. The eccentric nature of its editorial criteria is perhaps suggested by its treatment of May 20, 1936: Wikipedia’s entry records the implementation of the Rural Electrification Act but is mute concerning my birth. Go figure! The online annal for 1749 says nothing of Evans’s map or Philidor’s analysis, let alone of Hartley’s forgotten work on associative psychology. But there is one book that necessarily makes the cut: Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones. There can scarcely be more than, say, twenty plausible candidates for the greatest novel ever written, and this is one of them. There are not many seven-hundred-page books whose readers truly wish they could have been just a little longer. Like so many great books, like such competitors as Dante’s Commedia and Cervantes’s Quixote and Melville’s Moby Dick, it is the story of a road trip (remembering that in Old English one term for the ocean is “the whale’s road”). Tom Jones conquered the European literary world in 1749, and one of those conquered was François-André Danican Philidor, who seems to have read it while he was seeing his Analyze des Echecs through the press. If you have heard of him at all, it is probably because of the opera into which he later transformed the novel.

You have a first edition of Philidor!!!???

ReplyDeletePer John H. McWhorter in his "Nine Nasty Words: English in the gutter then now and forever," profanity has evolved from the theological, to bodily function and sexuality, until in modern times the most unspeakable and shocking words are those that are insulting and derogatory of classes of people. Great examples are offered!

ReplyDeleteThank you for your comment, which I think, however, you meant as a reply to the post about bastards (Bar Sinister). I did indeed read the McWhorter piece and much enjoyed it as usual.

Delete